|

Kangerlussuaq, Greenland - September 8, 2005

Suddenly, below us, appeared the coast of Greenland. After flying over this country so many times en route to or from Europe, gazing in wonder at the vast icefields of the central glacier and the deep fjords along the coast, we were finally going to descend and see this vast and mostly uninhabited country from ground level.

Today the airport is the busiest in Greenland and a major port of entry into the country for tourists, businessmen, and researchers. Because the ice pack is only 25km away, and accessible by road, it is the location of the operation center for the Greenland Ice Core Project Unlike the rest of the passengers, anxious to head off in search of muskoxen, I was hoping for a few minutes delay in boarding the bus at the airport. Nearby is the only geocache that would be accessible on our trip. It would have been great fun to navigate to the By the Musk Ox Cache and swap some Canadiana for an arctic trinket, but alas, the GPS reported the cache was 337 meters away, and the bus was almost ready to leave. One more reason to return. We passed the painted rock in the clue, and I knew we must have been within touching distance of the cache at that point. Our bus followed the dirt road from the airport into the Akuliarusiarssuk Mountains where one of the world’s largest herds of muskoxen has been slowly growing. In 1962, 13 young muskoxen were relocated here from northeast Greenland. In 1965 another 14 were added to the herd. There are now estimated to be 8-10,000 muskoxen in the area and there is a danger of overpopulation given the sparse vegetation.

With binoculars we scanned the hills and the shores of the glacial runoff Sandflugtdalen river for moving brown rocks, but the muskoxen, perhaps aware that the hunting season was underway, were not to be seen. We did see lots boulders in the distance which we dubbed MuskRox.

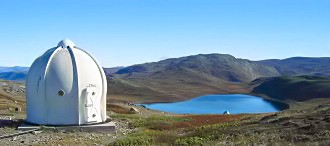

Not far from the airport is Ferguson Lake, known locally as Tasersuatsiaq. Surprisingly, the scenery below the lake is as interesting as the view above. This may have been our only opportunity to swim in a lake above the Arctic Circle, but we passed on it.

It's a pleasant place for a summer home. Cabins dot the shoreline and fishing boats are plentiful. It is not a new discovery. We examined evidence of a group of dwellings using the square stones of the area which may be as old as the Early Dorset. A short Zodiac ride from the port took us to our vessel, the M/S Explorer, our floating home for the next 11 days. Moments after the last Zodiac arrived we were under way. This was a first indication of the efficiency of the well-run ship we were lucky to have for our trip. As we steamed down the Kangerlussuaq Fjord, I noticed a speck in the distance. With binoculars, it appeared to be a black Zodiac following our ship. It didn't make a lot of sense. Did we leave someone or something behind? The ship was holding a steady 9 knots, but the Zodiac, at full throttle, was gaining on us. After fifteen minutes or so, the Zodiac came along the starboard side and the deck crane lowered a hook to the driver and passenger. Seconds later, the Zodiac swung in the air and was brought on to the deck, driver, passenger, baggage and all. Had we picked up Lara Croft?

We had picked up the real life Lara Croft. Here was a dimunitive, 5 foot 3 inch woman, dressed in leather and bloodstained clothes, armed with knives and guns, and a sharp Irish wit, ready for action. We didn't even know about the black belt in karate at that point. A woman who has been known to chase caribou on a snowmobile at 100 kilometers an hour, then take them down with her bare hands, Christine is not your average research scientist. She also enjoys eating the subjects of her research, and who can blame her. As she told Le Systeme Argos:

Kangerdluk means fjord and the suffix suaq means great, hence, Kangerlussuaq, the great fjord. At 175 km in length, the Kangerlussuaq is one of the world’s longest fjords. The Danes call it Sondre Stromfjord. Generally speaking, fjords are left by the retreat of a glacier that has carved a U-shaped valley to below the sea level. We sped down the calm waters of the fjord with the ebb tide, making 18 knots with the current, as the sun set. We enjoyed a fine meal in the dining room, toasting our crossing of the Arctic Circle, heading south for open water and the Davis Strait.

Continue to Day 2 - Tāterāt Glacier Links to more information:

|

From Ottawa, we looked down on solid cloud cover as we flew over the Province of Quebec, Labrador, and the Davis Strait and were beginning to doubt the

From Ottawa, we looked down on solid cloud cover as we flew over the Province of Quebec, Labrador, and the Davis Strait and were beginning to doubt the

From 1958 until 1992, a Cold War

From 1958 until 1992, a Cold War

During the

During the

We gaped in disbelief as

We gaped in disbelief as

It takes 2 snowmobiles to do it. The speeds at capture are around 40 to 60 km/hr. Prior to capture, speeds of 80 to 100 km/hr are not uncommon, for example when we are zooming in on an animal seen in the distance. One person on each snowmobile. I drive up along side the reindeer on one side and my Greenlandic assistant drives up on the other side of the reindeer. There is very little room between us at this point. Only room for the reindeer if we do it perfectly. I then reach out and put my arm around the reindeer's neck and we end up in the snow together. It usually takes less than 2 minutes (from the time we actually first sight an animal to when I have her in my arms).

It takes 2 snowmobiles to do it. The speeds at capture are around 40 to 60 km/hr. Prior to capture, speeds of 80 to 100 km/hr are not uncommon, for example when we are zooming in on an animal seen in the distance. One person on each snowmobile. I drive up along side the reindeer on one side and my Greenlandic assistant drives up on the other side of the reindeer. There is very little room between us at this point. Only room for the reindeer if we do it perfectly. I then reach out and put my arm around the reindeer's neck and we end up in the snow together. It usually takes less than 2 minutes (from the time we actually first sight an animal to when I have her in my arms).